Navigating Major Surgery

We recently concluded a study looking at a question prompt list (QPL) that older patients can use in preoperative discussions with a surgeon. The QPL is formatted as a three-panel brochure and is also available in Spanish. Findings from this study have been published and additional analyses of project data are ongoing.

We developed the QPL with an advisory council of patients and family members who had lived experience with major surgery. The council identified a need for better decisional support during preoperative conversations, including discussion of treatment options, postoperative expectations and advance care planning.

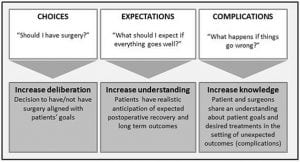

Specifically, they proposed three question categories:

- “Should I have surgery?”

- “What should I expect if everything goes well?”

- “What happens if things go wrong?”

Question categories and goals

We then adapted existing question lists to better meet the needs of patients considering high-risk surgery. The questions on our QPL are designed to empower patients to ask about — and deliberate on — the broader outcomes of surgery, not just individual risks or complications.

We received funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to conduct this work.

Learn more about the Navigating Surgery study.

Funding acknowledgement: This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (CDR-1502-27462).

Disclaimer: All statements in this webpage are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Best Case/Worst Case

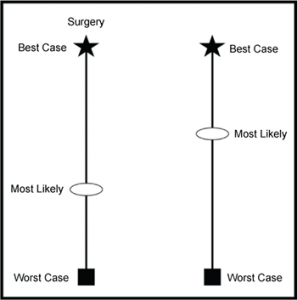

Our team is evaluating a communication framework, called Best Case/Worst Case that structures the decision-making conversation between patients and doctors. Best Case/Worst Case combines a simple pen-and-paper graphic and narrative description of treatment outcomes to help patients make difficult treatment decisions.

Each vertical line on the graphic aid represents a different treatment choice; for example, surgery vs. medical management, or surgery vs. supportive care.

The star at the top of each line represents the “best-case scenario,” the box at the bottom represents the “worst-case scenario,” and the oval represents the “most likely scenario.”

The doctor tells a story about what the patient’s life might look like in the best- and worst-case scenarios. He or she then incorporates evidence and knowledge of the patient’s clinical condition to estimate the most likely outcome and describe it for patients in a way that encourages deliberation.

We have already taught surgeons how to use the communication framework and evaluated our intervention with hospitalized patients facing serious surgical problems. We have found that Best Case/Worst Case helps patients engage in decision making and prepare for adverse outcomes. We have developed a training program to teach surgeons to use the Best Case/Worst Case framework and tested this with surgical residents across the country.

Currently, we are adapting the framework to help nephrologists discuss treatment options with patients considering dialysis. We are also collaborating with trauma centers across the country to evaluate Best Case/Worst Case for use with older adults who have suffered serious injury.