The term “from bench to bedside” describes a common vision of medical research programs. The goal is to take research insights from laboratory settings to practical applications in patients as quickly as is practical, and safe. Because surgeons work closely with disease pathology in the operating room, they have a distinct perspective that makes them uniquely capable of bringing this “bench to bedside” vision to reality.

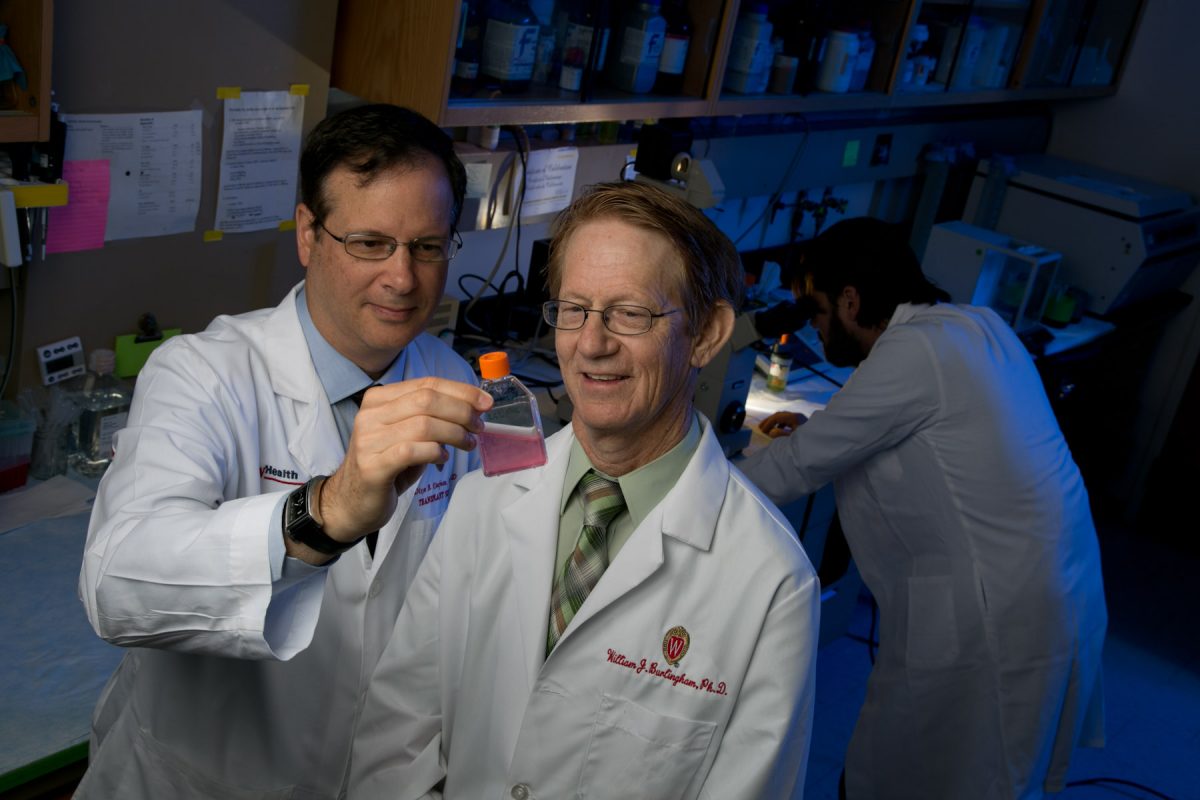

Immunology research in the University of Wisconsin Division of Transplantation, led by Dixon Kaufman, MD, PhD, Ray D. Owen Professor and Chair of the Division of Transplantation, exemplifies this vision.

“Our transplant surgery research teams can take basic discovery research in the lab to small and large animal studies, and then to an actual human clinical trial,” Dr. Kaufman said. “We encompass the whole research arc. We want to acquire the knowledge, test the knowledge, and then use it.”

And at the end of this arc? Better long-term survival for transplant patients.

Working Towards Tolerance

At the start of the path towards medical breakthroughs, scientists conducting basic research help us understand how human bodies or disease states work. Here at UW, Professor William Burlingham, PhD, is doing just that.

After a successful transplant operation, patients must take powerful drugs for the rest of their lives to tamp down their immune system, allowing it to accept the new organ. In addition to being expensive, anti-rejection drugs leave the person vulnerable to infections, metabolic disorders, and other toxicities.

“The goal of a transplant team is to be able to perform a transplant and have the person live happily without taking any drugs,” said Dr. Burlingham. Dr. Burlingham began studying how the body acquires immunologic tolerance in 1983.

“At that time, we were just trying to get the transplant to stay in with drugs,” he said. With advancements in transplant science, “Tolerance is now becoming a clinical practice.”

The Burlingham Lab studies mechanisms that affect organ tolerance, including tiny particles from cells, called exosomes. Exosomes released by the immune system are able to alert the body that something unusual is happening. While they can promote rejection of the organ in the short term, exosomes, especially those from cells of the organ donor, may be very beneficial for the transplant over time.

The scientists are investigating how these messenger particles carry signals to other cells, with the goal of modifying them in order to trick host immune cells into leaving the transplanted organ alone.

Large Animal Studies and a Medical Breakthrough

The next step in the arc from bench to bedside is to conduct trials that involve animal subjects. This important research allows therapies to be tested and studied in controlled environments, as Dr. Kaufman explores in his work. A prestigious National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant supports the Kaufman lab team’s efforts to reduce the need for lifelong medication after a kidney transplant. The lab is part of the Nonhuman Primate Transplantation Tolerance Cooperative Study Group, a collaborative, nationwide network of a dozen teams racing to develop new therapies to enhance long-term organ survival after transplantation.

Dr. Kaufman believes that large, diverse teams with active projects across the research continuum have a competitive edge in the quest for research funding. In turn, big grants can support multiple institutions across the country to reach research goals more quickly—together.

Building on techniques invented over a decade ago in the Stanford University lab of collaborator Samuel Strober, MD, the Kaufman lab developed a new model of kidney transplantation and donor stem cell infusion in rhesus monkeys. The lab has successfully performed a combination of two procedures that resulted in a phenomenon called mixed chimerism (where the immune system consists of a mixture of cells from both the donor and recipient)—leading to drug free acceptance of the kidney transplant.

Lynn Haynes, director of the UW Office of Research Compliance, was a researcher in Dr. Burlingham’s lab for over two decades.

Haynes coordinated the large animal study to assist with “orchestration of this tremendous project involving multiple collaborations across the UW and the country. It was exciting to put our research into a model that would lead to the next step of human clinical trials.”

To date, animals with even temporary mixed chimerism have been successfully weaned from immunosuppression drugs for as long as four years without kidney transplant rejection. This is a major medical breakthrough. Transplant patients are rarely able to stop taking immunosuppressive medication without rejecting or losing their organ transplant.

Human Studies and Pioneering Sisters

The final step towards medical breakthroughs is to conduct tests with human subjects in clinical trials. As part of a national study, Dr. Kaufman is now testing the mixed chimerism procedure for inducing kidney transplant tolerance in humans.

Last fall at UW Hospital, a pair of sisters from Platteville became the first people in Wisconsin to undergo this protocol. Doctors removed some blood stem cells from the sister who later donated her kidney. After the kidney transplant, they infused the cells into the sister that had received the kidney with the goal of establishing mixed chimerism. The procedure made the headlines (Wisconsin State Journal, Dec. 2, 2018).

Doctors anticipate that within 18 months post-operation, the sister who received the stem cells will become tolerant of her new kidney and be able to stop taking anti-rejection drugs. Soon, the pilot study will expand to include patients at 30 academic medical centers across the country.

Human clinical trials take a full team to succeed. This study is running smoothly thanks to the hard work and collaboration of a number of people, including clinical trial director Kristi Schneider, RN, MSN, ANP, Janelle McMannes, RN, the Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT) lab group, the trial sponsor Medeor Therapeutics, and the teams of Drs. Peiman Hematti, Professor and Director of the UW Health Clinical Hematopoietic Cell Processing Laboratory, and Kristin Bradley, Associate Professor of Human Oncology and Residency Program Director of Radiation Oncology.

Training for Future Transplant Scientists

Not only are our scientists driven to making discoveries that will eventually improve outcomes for patients, but they are also dedicated to training the next generation of surgeons and researchers in the process. Dr. Kaufman leads the Department’s NIH-funded Transplant Research Training Program, in which post-doctoral trainees spend two years conducting laboratory research to contribute to, and learn from, the entire arc of the research journey.

“Because there is such a limited supply of organs, we want people to be able to keep their transplants longer,” said Dr. Natalie Bath, a surgical resident and fellow in the program. In addition to honing critical skills such as analyzing test results and formulating research plans, she is learning how to interact with teams from other disciplines.

“I just sat in on a meeting with Dr. Kaufman’s research team. A hematologist and a veterinarian were present, as well as PhD scientists who specialize in certain tests. You really need this kind of multidisciplinary team to bring a project to clinical trials and treatments in humans.”

The training program, with its special focus on immunology and transplant tolerance, has given Dr. Bath experience in how the collaborative, bench-to-bedside research arc can succeed.

Promising Transplant Research in the Department of Surgery

Another lab moving transplant research forward through various phases in the research journey is that of Luis Fernandez, MD. His group has projects in the pipeline at several stages, stemming from their initial discoveries in the lab about how brain death in animals affects their organs. The Fernandez team is looking at how to block some of the destructive pathways using a protein called a C1-inhibitor. They are testing a procedure in non-human primates and have begun a pilot study in humans to see if the inhibitor can reduce the incidence of damage to a kidney transplanted from a deceased donor.

Transplant investigators are making strides in several other areas, including

- David Al-Adra, MD, PhD: Improving liver transplant survival using preservation under near physiological conditions of temperature

- Matthew Brown, PhD: Mouse model with humanized immune system to study human diseases

- Anthony D’Alessandro, MD: Clinical trial of new method for preserving organs under near physiological conditions of temperature for liver transplantation

- Luis Hidalgo, PhD: Endothelial biology and understanding mechanisms of antibody-mediated injury to organs

- David Foley, MD: Clinical trial of anti-inflammatory treatment to enhance kidney transplant function

- Joshua Mezrich, MD: The host microbiome in transplantation

- Jon Odorico, MD: Stem cell research for treatment of diabetes

- Robert Redfield III, MD: Strategies to reduce host rejection responses

- Hans Sollinger, MD, PhD: Gene therapy to treat diabetes

Prescription for Success

In the Division of Transplantation, Dr. Kaufman said, “We want to paint a model for how others should think about their work as well. We need principal investigators to be the quarterbacks and connect all the dots. We launch initiatives. They all start with discovery research. Then, if the research looks promising, we scale it up, and we stay on it for years.”

While the research arc is long and not without setbacks, the transplant research teams find inspiration in the promise of even longer, healthier lives for our transplant patients.

By Molly Wesling, PhD